On The ramp at AMS

Handling Northwest Flight 043 to Boston, Mass.

by Jan Koppen

|

You were clever to have specified a window seat when you made your reservations. Now you have put your jacket in the overhead-bin and having struggled past the occupant of 41B, you drop wearily into 41A. Gathering your composure, you glance out the window at the activity outside your aircraft, a Northwest Airlines DC-10-40 at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS). People dressed in blue dot the ramp, some drive various pieces of equipment, others rush about on foot. If you are an average traveler, you mentally classify them as “ground personnel” and turn your attention to something else. But wait! – Have a closer look at those men and women on the ramp. They are responsible not only for loading your luggage on board. But also, for the smooth, safe and on-time departure of your flight.

Passengers have become insulated from most airport activities. Modern terminals keep them away from windows that overlook the ramp areas and steer them towards the many retail stores instead. They almost never see the aircraft they are travelling on, because they board through loading bridges. I like to spotlight the work done by these legions of nameless people you never get to meet. Let’s look at a typical day working the gate through the eyes of a Northwest Airlines employee. It is about 0900 hrs. on Sunday, November 1992, and I am standing on the vast ramp at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS). A cold light rain is falling. I have interrupted my overloaded work schedule to catch up with some of the ramp activity.

Three hundred feet in front of me I see the familiar silhouette of Northwest DC-10-40, Flight 043 from Boston, Massachusetts, turn off the taxiway and onto the ramp. Today’s aircraft is N149US. Only a few months ago she was repainted in NWA’s new red and grey colored “bowling ball shoes livery”. This just to make her more appealing in the world of international air travel. She will be here for a couple of hours before pushing off again as Flight 042 back to Boston. The first responsibility for the ground personnel is to make sure the gate is ready for the flight. This is a joint effort by all involved, as the aircraft is unloaded, tidied up, stocked with meals, fueled and loaded again with outbound luggage and cargo. Waiting for her are more than a dozen blue uniformed KLM ground personnel (KLM handles NWA flights at AMS). After the marshaller has directed the aircraft to the correct spot and when the engines are spooling down, rubber chocks are placed before and behind the main wheels. Once the aircraft is secured this way, the airbridge is attached to the aircraft door number 12 and 11. As the doors open, the passengers deplane and immediately after a small army of men and women boards to sweep through the cabin, straightening and tidying up as they go. Anyone who boards an American registered aircraft, must undergo a thorough body search by security personnel. This is because of the threats by subversive elements of many nationalities. They are not idle threats, as the former Pan-American, among other, can assure you. Other ground personnel are also moving into action. A ramp agent (also known as a ramp rat) has raised a container loader to the forward starboard cargo door and is activating the DC-10’s on-board cargo loading and unloading system to roll the containers toward the open door. Each container, loaded with luggage, is lowered to the ground where it is loaded and locked onto one of the transporters strung behind a waiting tug, for delivery to the terminal. A belt-loader is placed up to the doorway of the DC-10’s aft bulk hold and then it is time for the ramp agents to perform. The cargo holds are one area a passenger never sees! The DC-10 aft bulk hold is only 5 ft (1.6m) high, so about the only way to work inside this hold is by moving about on your knees. And there is no carpeting on these floors! Inside the hold, the ramp agents must unload from 50 to 100 bags and /or often 2,000 to 3,000 pounds (750 to 1,120 kg) of freight and mail. There is little ventilation inside the hold and after 30 minutes of non-stop loading and unloading cargo and baggage, one is soaked to the skin, even on a cold day, much less a steaming hot day! Rep-cap (a KLM ramp officer position) Willem van der Linden and his crew have checked the load manifest which came off the teleprinter, so they know exactly what to expect. When the transporters are filled, an agent hops behind the wheel of the tug and heads for the inbound bag-room. Here, protected from the weather, is a roadway complete with curb and narrow sidewalk. The train pulls up to the two waiting baggage-handlers. Emerging from one opening in the brick wall and disappearing again into another opening is the shiny band of the luggage carousel. Just behind the wall is the baggage claim area where passengers are waiting for their luggage. One baggage handler starts the carousel and then both begin wrestling garment bags, suitcases and boxes from the train onto the carousel. At the same time the Cargo Department Services is assembling a long train of containers and pallets loaded with cargo and mail, which it delivers to their warehouses for clearance by customs and collection by forwarders and consignees. These operations are closely supervised by several NWA cargo agents. During a push, vehicular traffic on the ramp is staggering. Flight 043, for example, is surrounded by a belt-loader, two or three baggage train tugs with one to four carts each, a container loader and up to two dozen transport dollies, a lavatory service truck, a cabin service lift truck carrying cabin cleaning equipment, maintenance cars, the push-back truck and not least our VW Polo company car. In addition, the roadway immediately in front of the aircraft will soon be filled with a dozen or more vehicles rushing from flight to flight. Keep in mind; taxiing aircraft are nearby. Getting run over by vehicle doesn’t take much effort. The ‘gate’ certainly is no place for the absent mind! A jetliner engine is a major source of both immediate and long-term physical damage to ramp personnel. The wing mounted engines of the DC-10, hanging close to the ground, present a real danger of sucking you in or, at the other end, blowing you away, if not burning you to a crisp. Frequent training and company pamphlets emphasize the danger of jet intakes and jet blast. But being human, it is easy to forget. Jet engines may also cause gradual long-term damage. An airport such as Schiphol is a very noisy place and is deafening without proper hearing protection. The loss of hearing will probably not be noticeable immediately but is progressive and will be noticed overtime. When reading this, you may wonder” Why on earth are these guys interested in working on the ramp, gate or as a transportation agent for airlines?”. Let me explain; - Besides the need for a regular pay-cheque, there is the teamwork and the companionship. It is a lot like being on a sports-team. On the gate, everyone knows their job and it is a thing of beauty to watch how it all comes together. All elements for a quick turnaround fall into place like a jigsaw puzzle, without a wasted motion. No one needs to be told what to do next, - it just happens. Another pleasant aspect of being an agent is the ability to rotate duties from day to day, so each shift is a little different. Finally, the ramp has its own style of humor, much of it directed at rookie agents. As thousands of neophytes before them, new agents are still being sent on laughable errands. Due to the primarily male environment, much of the humor is of the locker-room variety. However, most of it is self-directed and everyone is fair game. People with thin skin don’t last long if they can’t laugh at themselves. Activity on the ramp quickens. Now, KLM ground handlers are preparing Ship 1145 for her return flight to Boston. All flight-line maintenance is also supplied by KLM. Their constant technical support keeps our dependable DC-10s flying under all conditions. KLM Catering has finished stocking the galleys and their lift-body truck backs away. For all NWA flights from AMS, KLM flight operations is responsible for the aircraft’s weight and balance determination. Their load planners, often a woman, obtain the business and coach class passenger counts. Company regulations say a passenger weights 170 pounds (63.5 kg) and carries 1.2 bags, each weighting 33 pounds (12.3 kg). Thus, 100 passengers and their luggage add an estimated 20,960 pounds (7,822 kg) in weight to the aircraft. In addition to these figures, the load planner obtains the weight of mail and cargo on the flight, and the weight of fuel. Operations is also responsible for a proper fuel balance. The fuel weight in one wing must not exceed the weight in the other wing by more than a predetermined percentage. All this data is entered into a computer which sends it to Northwest’s mainframe computer in Minneapolis. A minute or so later the teleprinter comes to life, printing the loading instructions and the DPWM (Display Passengers Wait Manifest) for the flight. The loading instruction tell the red-cap how much weight can be placed in the DC-10’s aft bulk hold and gives the exact positions of the outbound luggage and cargo containers and pallets. The DPWM is more complex. It shows how the empty weight of the aircraft, plus the estimated weight of passengers and cargo, plus the weight of the fuel, are totaled to derive at the actual takeoff weight of the aircraft. The computer also factors in weather and runway conditions and provides suggested flap settings for takeoff. A copy of the DPWM is therefor delivered to the cockpit crew and other copies are filed. Baggage handlers in the out-bound bag room have been assembling the luggage for Northwest’s Flight 043. The bags arrive on conveyer belts from the check-in counters. Colorful luggage tags with the designator BOS help the baggage handlers direct these items, after a thorough X-ray check, into containers for the flight. Once those containers, already on their transporters, are packed, they are towed out to be loaded onboard. At the same time several containers and pallets with cargo arrive from the cargo warehouse. Occasionally this cargo includes what the loading instructions designate as a “HUM”, for human remains. Coffins and their contents are given special treatment. At the air cargo facility, they are placed in carriers called “air-trays” to ensure their safety on the flight. Other outbound cargo needing special treatment includes live pet animals. They are placed in “pet porters,” which are securely strapped in the aft bulk hold. The flight crew will be well-informed to provide proper heating and air flow during the flight. With the final freight pallet stowed into the hold, the high loader is disconnected, and the huge hydraulic freight door is closed and secured. The passengers have finished boarding by now and the DC-10 is ready for push back. KLM ground engineer Donald van Tongeren plugs in his interphone to establish contact with the flight deck. Inside, the crew is preparing the aircraft for engine start-up. Due to a minor technical snag, start-up takes place this time with the help of a ground power unit, the air pressure Houchin starter. Donald signals the operator to increase the air pressure and abruptly the starter’s low hum changes into a high-pitch blare. Highly compressed air forces the second stage compressor of the Pratt & Whitney JT9D-20J turbofans to accelerate to idle speed. Moments later kerosene flows into the combustion chambers and simultaneously the plugs are fired. With a small explosion, Number 2 engine comes alive. As it settles down to idle power, the characteristic rumble-into-whine starts to fill the upper level of my hearing range. Quickly the starter is disconnected and while the mainwheel chocks are being removed, permission to push back is being granted by Ground Control. With a puff of black smoke, the monstrous, weary looking but powerful Hobart push-back truck starts to do its job. In the cabin, the more experienced traveler recognizes the telltale tremble as the truck overcomes the inertia and begins to ease the trijet away from the gate. Almost 400,000 pounds (149,280 kg) of airplane, people, fuel and cargo are gliding backward across the oil-stained concrete of the ramp, with Donald walking alongside, his line still connecting him to the flight deck, ready to report any problem to the crew. Once at a safe distance from the terminal, the truck stops and the tow bar is disconnected, placing nosewheel steering under direct control of the cockpit again. Engines one and three are started in sequence with power provided by Number 2. The truck heads back to the terminal, Donald disconnects his interphone and walks to a position from where there is visual contact between him and the captain. With a “thumbs up” signal, he indicates the all-clear and that the aircraft is ready to go. As the engines settle into their pre-taxi idle, he salutes the cockpit and walks back toward the terminal. As a gesture of thanks to the ground crew, the flight crew flashes the DC-10’s taxi lights several times. Then, with a sudden roar, the three big turbofan engines spool up and the aircraft is on its way. As the hot exhaust gases are blasted backward, they are caught by the jet fences to prevent doing harm. As Flight 043 heads for the active runway, 24 this day, and reaches the holding point, I look at my watch and realize I must head for the office …. but - “What the heck, let’s enjoy the show!”. Suddenly the sound rises to a furious level and the three-holer responds to the demands from her engines. Slowly she starts to build up speed. With already 3,000 ft. (915 m.) behind her, the DC-10 is still rolling at about 170 mph. (273 km/h.). Then the nose slowly rises, as if sniffing the sky while she hurtles along, until, moments later, she lifts off. She roars over the threshold and past the building on the adjacent A4 motorway … Northwest 043 is GO, back to the Western Hemisphere. |

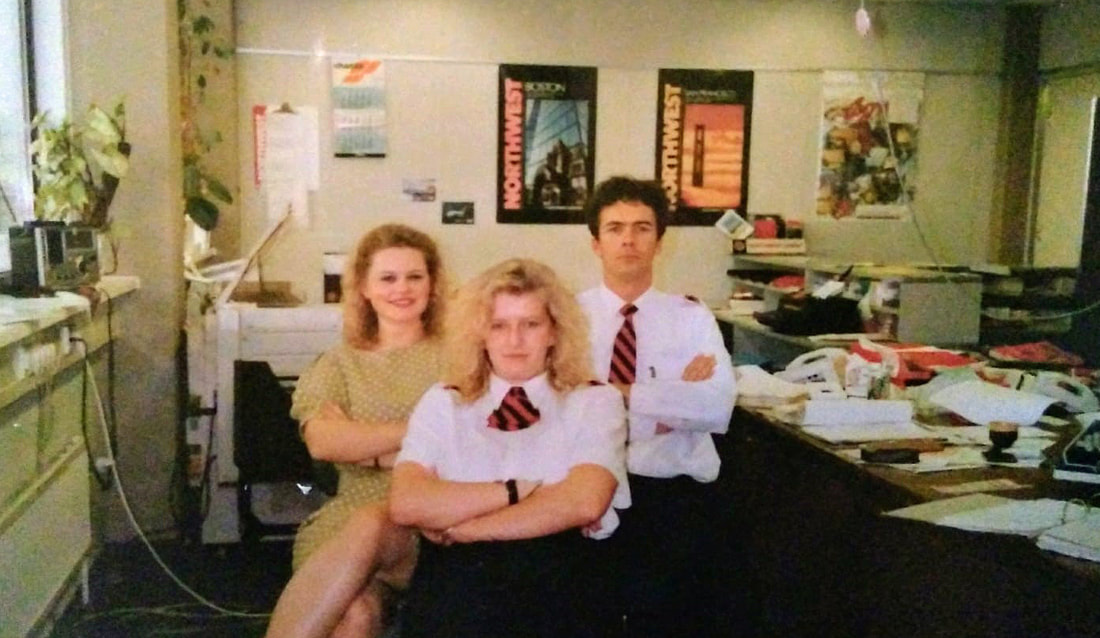

Nothwest staff working at the gate of Amsterdam Schiphol Airport during the early 90s.

First flight on July 2, 1974, and delivered to Northwest Airlines on August 9, 1974. Withdrawn from use and sold to the FAA on January 1, 2002 for testing at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Maryland. Here is taken at McDonnell Douglas plant before delivering to Northwest.

Aside from Pan American and TWA Northwest Orient was the only other US trunk airline with enough of an international network to justify large numbers of long range widebodies. Orient had been a long time Douglas customer until the 1960s, having operated DC-3s, DC-4s, DC-6s, DC-7Cs and DC-8s. Its experience with the Eights wasn’t satisfactory and Douglas lost out to Boeing throughout the 1960s as Northwest acquired substantial fleets of 707s, 720s and 727s. Northwest bought both the 747 and the DC-10 but they weren’t interested in the General Electric powered DC-10-30 long-range variant that would eventually form the majority of orders. Their CEO Donald Nyrop famously said at the time: “If I want a light bulb, I’ll go to GE; if I want an engine, I’ll go to Pratt & Whitney.” So to keep Northwest, and Japan Air Lines, happy McDonnell Douglas designed and built a new variant to be called the DC-10-20. This was to be equipped with the JT9D-15 turbofan but otherwise matched the GE powered DC-10-30. In the end the engines were JT9D-20s and the variant name was changed at Northwest’s request to the DC-10-40 so it would seem like a newer variant than the series 30, and Northwest could boast about it. McDonnell Douglas certainly went the extra mile to keep the customer happy! Northwest Airlines DC-10-40, N149US, fleet # 1149, still in "Orient" colors, taxies up to the gate at AMS.

Ship # 1149 was parted-out and finally scrapped during 2005 at Greenwood, Mississippi. Ship # 1158, alias N158US, left the Long Beach factory in 1974 and has spent her entire its life with Northwest flying on the company's far-flung network. During 2002 she was retired from service and ferried to Greenwood, Mississippi, for part-out and scrap which was completed in 2005.

"The Northwest Girls" having fun at the company's ticket office

Posing in front of the camera are my Northwest Cargo co-workers at our NWA Cargo office at Schiphol airport during the early 90s. Katja Eckstein (in the middle) is still working for KLM Cargo.

Cargo Agent Magteld van Schaick working ship #1150 which was a DC-10-40. The yellow VW van was her private car! Nowadays impossible by all security issues. ‘1150’ was parted-out and finally scrapped during 2005 at Greenwood, MS. (Amsterdam Schiphol, early 90’s).

Every day scene at Amsterdam Schiphol airport during the 90s. Schiphol was the main european hub for Northwest airlines.

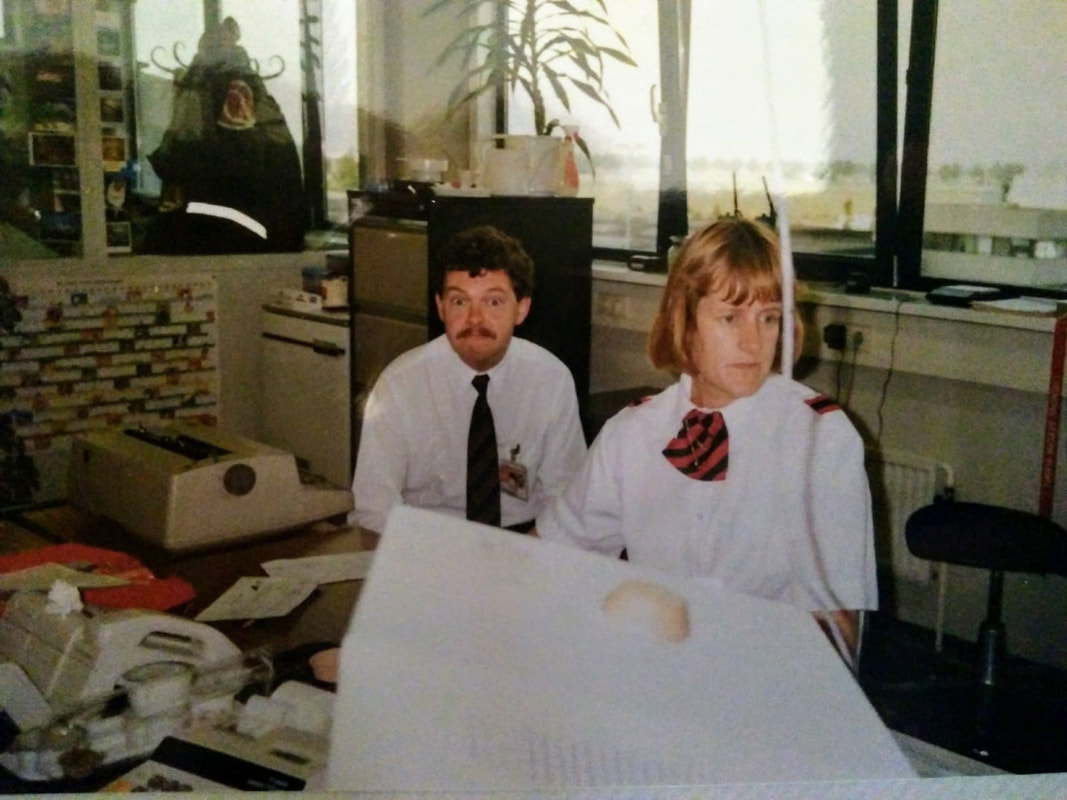

NWA Cargo manager Jacques Sol and Cargo Agent Magteld van Schaick at work in our office, which was situated in Aero Ground Service cargo flat.

The author at work, supervising the handling of Ship # 1149, during the early 90s.

Then, with a sudden roar, the three big turbofan engines spool up and the aircraft is on its way.

Most DC-10-30s clocked-up more than 126,000 flying hours before retirement. During the last decennium many of them were parted out and scrapped at Greenwood, Mississippi, by The Memphis Group. |

After their service live, many faithful members of the glorious Northwest DC-10 fleet are coming to a close at Greenwood, Mississippi. Seen here are several NWA DC-10s being parted out and scrapped by The Memphis Group during the last decennium.

Photo credit: Bruce Leibowitz.

Photo credit: Bruce Leibowitz.