My first flight, my first emergency

By Capt. Fernando de la Torre Bekdach

|

A few months ago, I accepted a position as a Flight Engineer with Ecuatoriana de Aviacion (now extinct), the Ecuadorian flag line. I just finished my training and passed the check ride. Everything was new for me.

I arrived in Ecuador after being in the USA for five years studying and working in aviation. It was what I wanted to do since I could remember. I validated my commercial FAA pilot's license with instruments and multi-engine for the Ecuadorian aviation authorities. It was quite a process full of frustrations since everything was so different in the procedures. Once I acquired the license, which was a validation, I went out to look for the job I had always wanted. Unfortunately, it seemed impossible since I never got the long-awaited job with only a few hours of flight and without knowing anyone in the aeronautical environment. Reading the newspaper, it informed me that the state company required co-pilots and flight-engineers. Since I did not qualify as a co-pilot, I decided to apply as F/E since I also had an FAA license as an aircraft maintenance engineer. There was no problem, and I became the youngest F/E in Ecuador and the only one who was also a pilot since the rest were maintenance and operations people. In the USA, you had to be a pilot to be a F/E in the airlines. My first flight, without an instructor, as flight engineer was a Saturday in March 1980. I was all excited and happy for the success obtained. There I was, that early, cold morning, wearing my new black uniform with a white cap, my two yellow stripes on the shoulders of the shirt, and the sleeve of the uniform. I was more than proud, and a dream came true to fly as a crew member in an aviation company. In this case, the largest in Ecuador. The flight was QUITO-GUAYAQUIL-LIMA-GUAYAQUIL-QUITO in a Boeing 720, a smaller variation than the B-707. I already knew which crew was flying with me, and I was happy since the Captain and the Co-pilot was young too, and I knew them. The cabin crew was five girls, all very young, and I only remember the supervisor's name. When I arrived for the "briefing," it was still dark. Already in the operations room was the Captain who welcomed me and informed the rest of the crew that this was my first solo flight. I thought the cabin crew got a bit nervous. Commander Diego Chiriboga, a young man of about 35 years old, was a relative newcomer in command of the aircraft, but he already had a lot of experience. Over the years, he became an instructor and the training director of the airline. The pilot training changed a lot for the better with him. He checked me out on the B707 as co-pilot years later. I also flew with him on the DC10-30 and the A320. He flew DC-3s, DC-4s, DC-6s, Electra's, 707/720s at that time and in the future was to fly the DC-10, Boeing 737, A320, A340, Boing 777, and near the end of his career, he became a Boeing 777 instructor in Korea. The co-pilot, Leonardo Guzmán, had just been checked on the plane; he had no more than 50 hours on it. We were from the same class, we did the ground school together, he was about 32 years old, and he was a pleasant guy. He liked to be joking all the time. He flew a lot on the 707, DC-10, A310, 727 and ended his aeronautical career as Commander of A320. He finally became director of operations of TAME (an airline in Ecuador now extinct). He made history in Ecuadorian aviation since he made the last flight from Quito's old airport (SEQU). He was the first Ecuadorian pilot to land in Quito's new airport, Tababela (SEQM). The supervisor, Patricia Aulestia, was of my age, 26 years old, and had a lot of experience. She was a pretty girl. Her sister was Miss Ecuador, and her father, a retired General from the army, became Minister of Defense of Ecuador. She had a cousin who was a co-pilot in the airline who years later would become a commander, known as negro (black). After the required briefing, we proceeded to the aircraft; we did our checks, and in my case, a little nervous because it was the first flight. I emphasized everything, and I felt that maintenance, operations, and dispatch personnel were looking at me and commenting on my first flight. The flight to Guayaquil's Simon Bolívar airport (SEGU) takes around 30 minutes, a short and routine flight for the airline, the plane had arrived from Miami, and we had passengers in transit and others to Lima. Doors were closed, we had about 60 passengers, and everything was normal. Leonardo, the co-pilot, was the "pilot flying." The old Quito airport has an altitude of 9.260 feet above sea level, and the runway is 10,000 feet long. We took off from runway 35 to the north and had to make a 90 degree turn to the right while ascending since in front there is a small hill called Casitagua. The instrument departure SID QIT 9, which was with a DME arc, was executed perfectly. We soon reached our cruise altitude of FL 180. With all checks done, I contacted Quito and Guayaquil's operations offices, informed our ETA (estimated time of arrival), fuel to load, how much the payload was for Lima and notified us of the pre-weight and balance. We certainly had sufficient time for a coffee and a smoke in the GYE/LIM sector. The pilots changed frequencies and got the weather conditions (at that time, there was no ATIS) for the arrival. Together we reviewed the descent, approach, and landing. The briefing proceeded with the help of the SEGU Jeppesen chart. It would become an ILS NDB approach to runway 21. The descent began 70 miles out of GYE after the San Carlos position. We were authorized to descend to 10,000 feet at 40 miles in the Catarama position. Then we changed frequency to approach, and they allowed us to descend to 2,000 feet directly to the PAL NDB. Leonardo did everything well, reducing the speed of the landing configuration. The plane was ready to lower flaps and landing gear far back to pass the PAL beacon. Fully configured and landing speed to intercept the glideslope, Leo called Flaps 20 the first position. Looking at his MHPDI (magnetic heading visual deviation indicator), he commanded flaps 30 and gear down. My function as F/E was to ensure that everything was optimal with each movement of the controls, switches, or levers. I was surprised when the Commander lowered the landing gear lever to see the instrument panel's hydraulic quantity decrease instead of increasing. I shouted to the pilots, "we are losing the hydraulics." The Commander remarked sharply; -"close the valves," which I did immediately. We only had approximately a gallon of a remnant, and we were at 2.000 feet and 2 miles out of the PAL beacon, which is the FAF (final approach fix). The Commander asked ATC for a holding pattern, which we were authorized. At that moment, I informed the two pilots that we had three green lights and one red, that the left gear door was open and that we were keeping 30 flaps. I looked for my checklist because we had to fix the door. If would land in those conditions, the door could be smashed on impact and could destroy the plane's structure. At that moment, Diego the Commander spoke to me. In his eyes and facial expression, I saw the concern that his Flight Engineer Fernando, on his first flight, in line with 60 passengers and crew, had to solve this problem, THE EMERGENCY. Diego informed Guayaquil Approach the control and the passengers about the situation. He declared an emergency, and we were holding in the vicinity of the PAL marker at 2.000 feet while the Flight Engineer had to solve the problem! Patricia enters the cabin and informs that the passengers are advised and secured in their seats. Diego told me to get out of the cockpit and check the landing gear's position and the door through one of the passenger windows, which is impossible. At this moment, the training and, most importantly, having read and understood the manual comes into work. On the technical part, 707/720 had a cut in the carpet and some visors at the landing gear's height in the middle of the passenger cabin for cases like this to see how the doors are. I had to go out and do this procedure that I had never done, and as I said, it was in the manual, and the worst thing that they did not train us is the human part, how to deal with passengers in cases like this. There he is, the FE with a baby face leaving the cockpit on his first flight to the passenger cabin to kneel and lift the carpet in front of all the passengers; at that moment, they all get up and begin to ask what the problem is, and there are some who they think to know more than the crew. The only thing left to do is exercise authority and order the passengers to stay secured in their seats, which I did, and everyone was calm; I thought some nuns had already begun to pray the rosary. Indeed, when I lifted the carpet and looked through the viewer, I saw that the left landing gear door was open; I returned to the cockpit and informed Diego and Leonardo of the situation. The other problem to solve was the position of the Flaps and Slats. With hydraulic pressure, the trailing edges were at 30 degrees, as the holding speed was low, there was no problem, but it had to be solved. The good thing is that the trailing edge flaps had an alternate electrical procedure. I retracted them, but the slats stayed extended, and there was already a speed limitation. Of course, the Captain asked his F/E what to do with the door problem, I am supposed to be his technical advisor, and I have to give him an accurate and sure answer. I told him that we still have one gallon of hydraulic and pressure; I suggested that if we open the valves and with that little amount of fluid and pressure, the door would close; he stares at me and tells me that it will work for sure. I said, - NOT sure", but it is the only alternative to what is left at that time or land and destroy the door." He gave me the order to open the valves. I did it, and 'BRAVO' the door closed. One less problem and stress. We were still holding and burning fuel, but the airport was only 7 miles away, so no problem. The problems did not end yet; the nose gear was not secure since it did not have sufficient hydraulic pressure, and we had to do a procedure in the manual. They had explained us during ground school training, but we had never done or practice it. There is no way to do it, even in the simulator. It is quite a procedure; those B707 / 720 aircraft have the electronic compartment under the cockpit, which we called the lower 4. Here there's the whole structure of the nose gear, with some pulleys to which you have to move them with a device called the "Johnson Bar" and drop a pin into a slot to secure the nose gear. First, raise the navigator's seat, open the floor door to the electronic compartment and go down to the famous structure. They're supposed to be a spotlight, but it was all dark. Like a good F/E and pilot, I had my flashlight with "D" batteries, and I arrived in the desired place. I found the famous bar and read the instructions that were attached to the structure. Inside me, there was the question, I have never done this, not even in the simulator, and if I am doing it well, then I turn the pulleys. Everything started to move, and again by the grace of God, the pin falls vertically in the slot, and voila, it finished the procedure. I began returning to the cockpit, but I am uncertain if it will be okay, so I returned to check again and if it was still in its position. The Captain already called me a few times with a nervous voice. I got back to the cockpit and told him that everything was in place and that he could start the approach so that we could be in a few minutes on the ground. To my surprise, the Captain informed me that we were returning to Quito. Company's order. I told him that we didn't have much fuel, the gear was down, and the slats extended, but orders are orders; we climbed to FL160 at low speed and returned to Quito's runway 35, a visual without any problem. We stopped on the runway and towed to the maintenance ramp. Everything went well, the training, the study had paid off! Forty years later, I wonder, why if being in front of the Guayaquil runway at 2.000 feet and a few minutes from landing, we ordered to fly 152 NM to a high altitude airport in the middle of volcanoes, with difficult access in those conditions. The checklist at that time did not have what it says today on modern aircraft when you have such a problem; - 1/. LAND ASAP. 2/. LAND AS SOON AS POSSIBLE. 3/. LAND AS SOON AS PRACTICAL. Forty years have passed since this was my first flight as a professional pilot and crew member; now retired and alive, I thank all those pilots with whom I flew and shared the cockpit. We knew how to be disciplined and study the planes that we had to fly all these years. Today we can tell this and many other stories and anecdotes about our lives as aviators. Capt. Fernando de la Torre Bekdach (retired) |

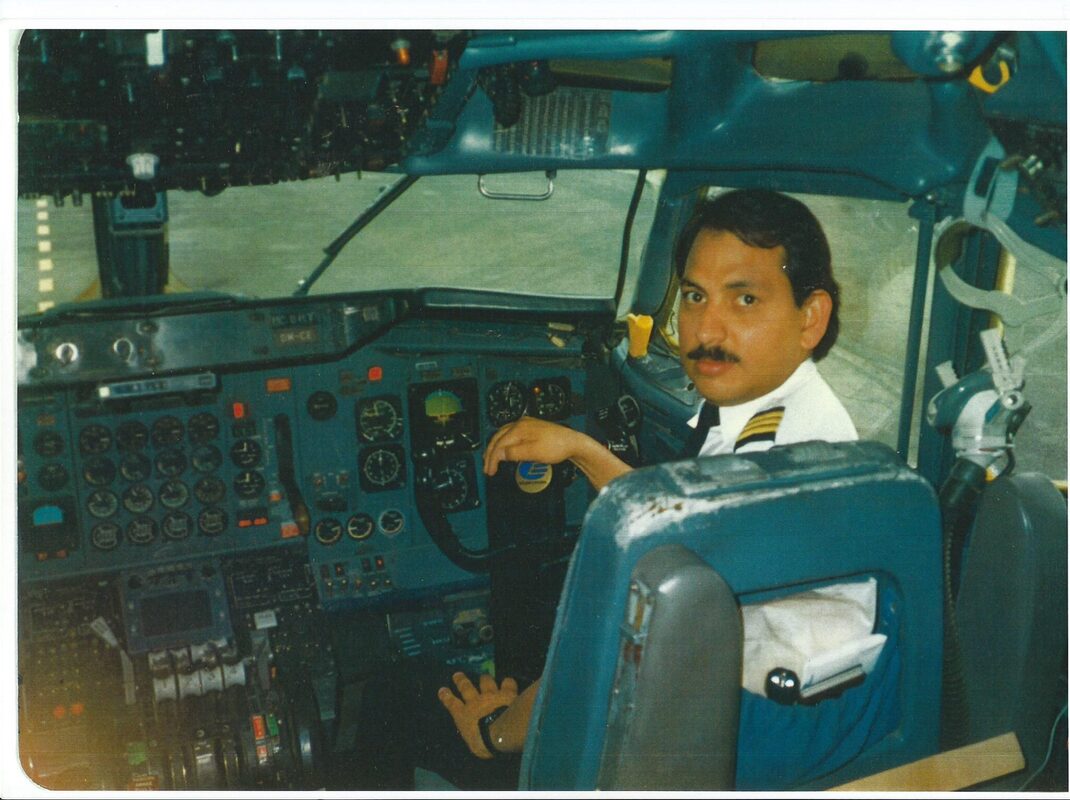

Me as F/O at the helm of Ecuatoriana Airlines Boeing 707-321B HC-BHY in 1990.

Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP at Quito. Artwork on the aircraft is by Bolívar Mena Franco.

Photo credit: Rene Francillon. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP on push back at a unknown airport.

Photo credit: Unknown. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZO, taxying out at Miami, bound for Guayaquil, in April 1977.

Photo credit: Fredy. Boeing 707-321B HC-BCT nears the threshold of runway 17 at old Quito Mariscal Airport one day in December 1980.

Photo credit: Rob Hemelrijk. Ecuatoriana Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP is seen here blasting out of JFK Airport on a dull day in July 1976.

Photo credit: Ken Rose Boeing 720-023B HC-AZO Miami, November 01, 1978. Delivered in 1961 to American Airlines as N7551A and seen here wearing one of 5 diferent special colours Ecuatoriana Airlines introduced in the late 1970's to represent the diferent Ecuador regions.

Photo credit: Mesquitta Colection. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP taxying out for departures, in October 1979, with Miami's corrosion corner in the background.

Photo credit: Bob Polaneczky. Boeing 707-321B, HC-BFC takes a break at Miami in the summer of 1981.

Photo credit: Micheal Prophet. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP smokes down at the runway.

Photo credit: via Capt. Fernando. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP smoking out of Bogota-El Dorado in the late '70s.

Photo credit: via Capt. Fernando. Opened in 1960, Quito's original, high-altitude airport had a cramped runway surrounded by the city that made landings challenging for pilots and nerve-wracking for both passengers and residents living in the surrounding neighborhoods. They were right to worry, as almost a dozen serious accidents took place at the original Mariscal Sucre Airport over the years.

Photo credit: Barry Curtis. Boeing 720-023B HC-AZP during the part out process at Marana Pinal Air Park, in March 1987.

Photo credit: Jon Protor (RIP). An aviation enthusiast who I always admired! |

If you enjoyed this story and you want to publish your own aviation memoires, do not hesitate and contact me at [email protected].